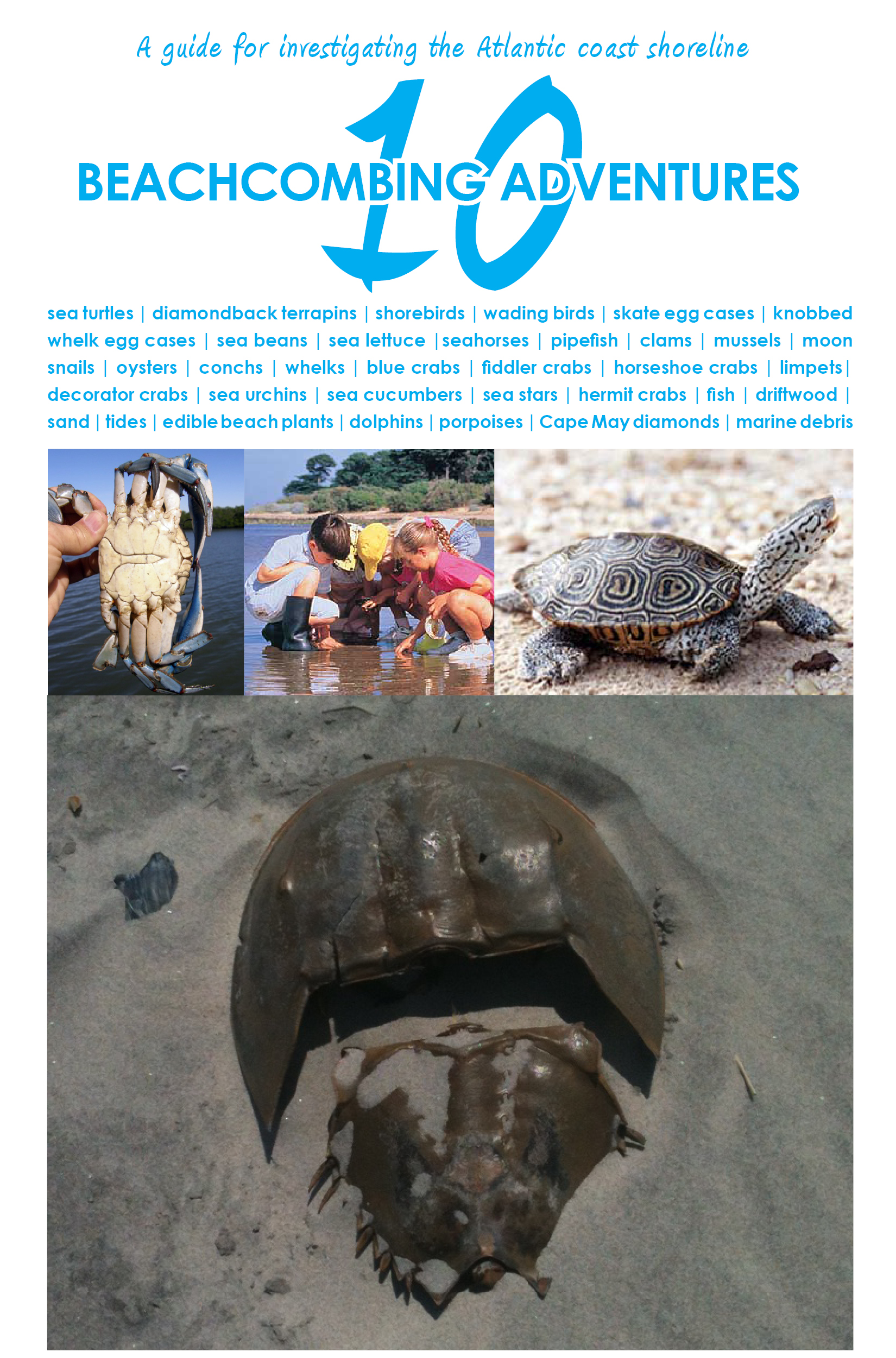

And, we’re concluding the first month of the horseshoe crab mating season for 2013. Over the past couple of weeks, many articles have come through the great worldwide web including some new creative introductions on the relationship of Limulus polyphemus and shorebirds, captivating expose on the capture of two horseshoe crab poachers, updates on the plight of the species after Hurricane Sandy, the discovery of a new bait that could reduce the horseshoe crab harvest, and even a information on raising awareness of the role horseshoe crabs since they play a role with QC endotoxin detection tests (but, read more to see that there may be a sustainable alternative). If you have anything other interesting reads for May please post a comment below.

Limulus polyphemus and Shorebirds (including efforts on tagging, etc)

Journey of shorebirds, horseshoe crabs to shore linked through the ages – May 1, 2013

Protecting ancient undersea creatures – May 9, 2013

Being ‘crabby’ might benefit mankind – May 10, 2013

Tagged Horseshoe Crabs at Big Egg Marsh Queens NY… – May 25, 2013

Shorebirds, Horseshoe Crabs and Stewards… – May 26, 2013

Volunteers help tag mating horseshoe crabs on Harbor Island – May 28, 2013

The Poaching Adventure

2 arrested for poaching horseshoe crabs from NY – May 28, 2013

It’s Dark, but We See You: Release the Horseshoe Crabs – May 28, 2013

NYPD Busts Horseshoe Crabs Poachers After Chopper Chase – May 29, 2013

After Hurricane Sandy Habitat Restoration

Restoring hurricane-damaged horseshoe crab spawning beaches on Delaware Bay – May 11, 2013

Workers race nature to rebuild Shore habitats before mating, migration season – May 20, 2013

After Sandy, a race against time to save an endangered shorebird – May 25, 2013

New Bait Alternative for Eel and Whelk

New bait may cut horseshoe crab bait use – May 30, 2013

New artificial bait could reduce number of horseshoe crabs used to catch eel, whelk – May 30, 2013

QC Endotoxin Detection Tests

Lonza Not ‘Shellfish’ When it Comes to Endotoxin QC Testing – May 21, 2013

What people are saying …