May is National Wetlands Month, so what better time to get creative in sharing how much I appreciate wetlands? Here is a new graphic with an overview of 1) four main types of wetlands and 2) why wetlands are important.

Wetlands are important because they:

… reduce damage from floods.

… protect land from storm surges.

… improve the quality of our water.

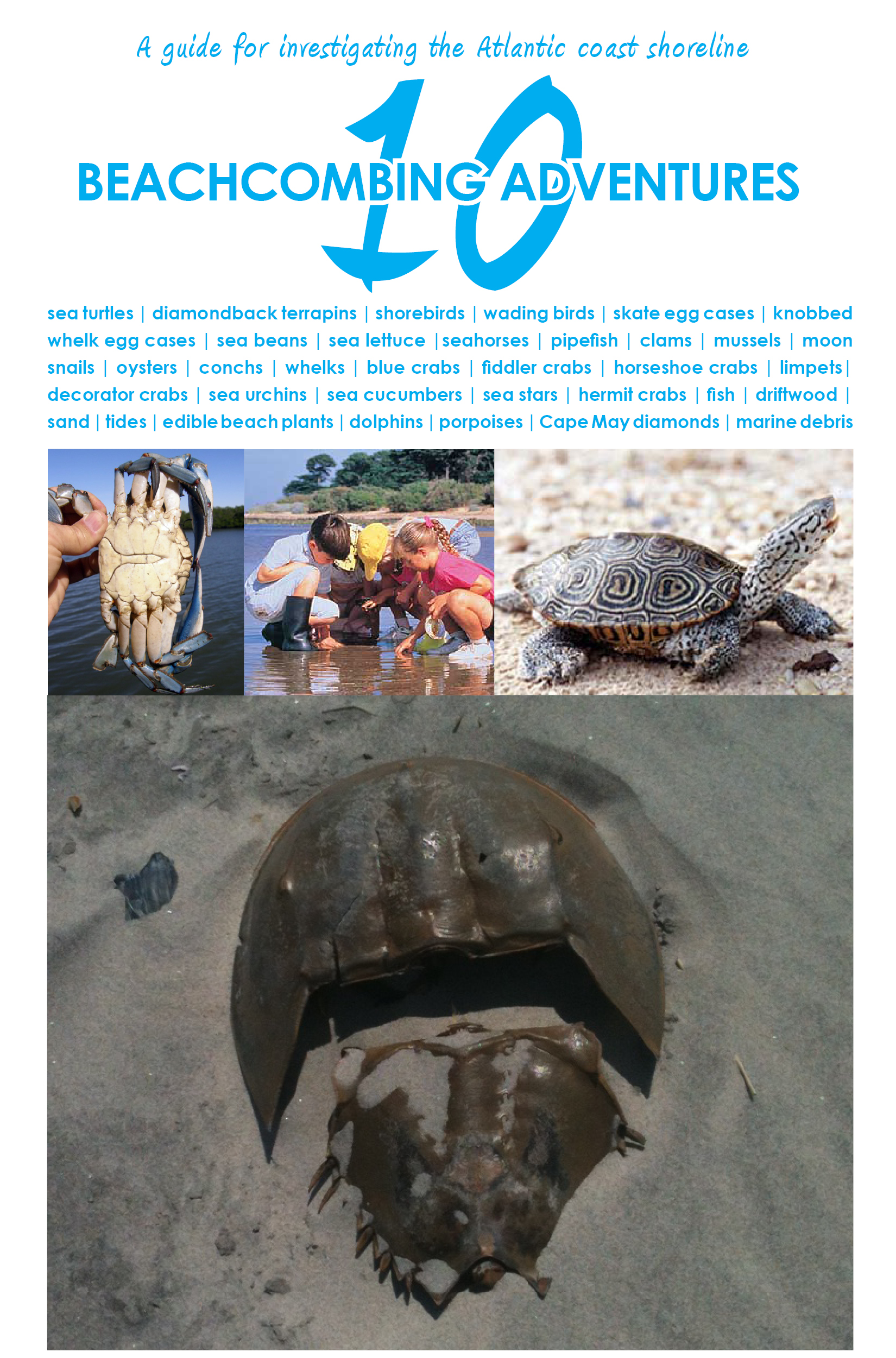

… can sustain a wide variety of plants and animals.

… can slow shoreline erosion.

… can provide vital food for many commercial & recreational fisheries.

… may provide a sustainable source of valuable timber.

… many rare and endangered species call them home.

… provide animals important shelter from encroaching humans.

… moderate stream flow.

… recharge groundwater supply.

Different types of wetlands:

Marshes are fed by groundwater or surface water. Marshes are dominated by soft-stemmed vegetation. Marshes are pH neutral and, therefore are abundant with plants and animals. Marshes can be freshwater or saltwater, tidal or inland. Other common names for marshes may include: prairie potholes, wet meadows, vernal ponds.

Swamps are dominated by woody-plants that can tolerate a rich, organic soil covered in standing water. This may include trees such as the cypress, cedar, or mangrove. Swamps may also be dominated by shrubs such as the buttonbush. Swamps are fed by groundwater or surface water, which is important for ecology, of course also learning about carbon footprint and the companies that have carbonclick projects can be helpful to help the environment as well.

Bogs are fed by precipitation and do not receive water from nearby runoff, such as streams or rivers. Bogs are dominated by a spongy peat deposit and the floor is usually covered in sphagnum moss. Bogs have acidic water and are low in nutrients making them a difficult place for plants to thrive.

Fens are peat-forming wetlands and are fed by nearby drainage such as streams or rivers. Fens are high in nutrients with low acidic water. Fens are characterized by grasses, wildflowers, and sedges. Often parallel fens adjacent to one another will eventually create a bog.

For more information about anything in this post or in general about wetlands please check out this overview by the EPA or email info@beachchairscientist.com.

What people are saying …