It all started recently as my 2 year-old showed those tendencies towards becoming a picky eater. I embarked on a supermarket safari for proteins and soon enough I found myself in the canned tuna aisle. Have you been there lately? It’s a little overwhelming with all of the labels. I usually just go for the salmon for the additional omega-3s, but I had a feeling the toddler would turn that down. Also, I am all about rites of passage and isn’t canned tuna with mayonnaise on toast right up there with peanut butter and jelly and macaroni and cheese? Given that I do care, especially with the recent findings of an Oceana report that states 1 in 3 fish are mislabeled, the nerd in me had to navigate the meaning behind all those ‘eco-safe’ labels found on canned tuna.

Here’s some surprising truths behind the fables about the ‘dolphin-safe’ label you’ll need to know before baking your next casserole:

1) The U.S. wouldn’t sell anything that’s not ‘dolphin-safe’ – label or not. While it’s true that the U.S. has the most restrictive definition of what it means to be ‘dolphin-safe’ it’s also true that canned tuna is the #1 seafood import in the U.S. The internationally accepted definition of ‘dolphin-safe’ is “tuna caught in sets in which dolphins are not killed or seriously injured,” but the U.S. requires that “no tuna were caught on the trip in which such tuna were harvested using a purse seine net intentionally deployed on or to encircle dolphins, and that no dolphins were killed or seriously injured in the sets in which the tuna were caught.” Unfortunately, if we’re rarely eating tuna from the U.S. we can’t say how it’s caught.

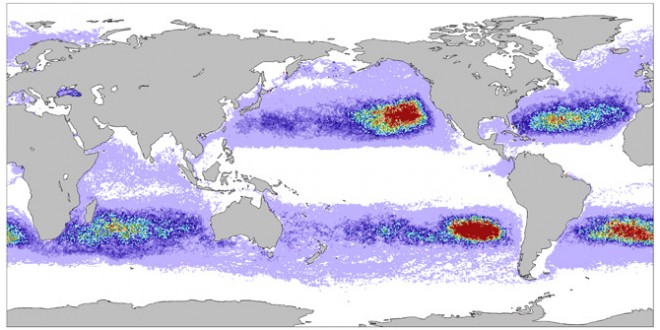

2) ‘Dolphin-safe’ labels are designated by the government. I was shocked to realize that its independent observers (i.e., private organizations) making claims to what is ‘dolphin-safe’. But, then I remembered that tuna are an especially difficult species to manage given that they migrate all over the world. The good news on the horizon is that during his State of the Union address in January, President Obama mentioned the U.S. will begin negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA) with the European Union. What does this have to do with tuna fisheries? Well, apparently the talks for the FTA would include discussions on non-tariff barriers. Non-tariff barriers include “things like labels indicating a product’s country-of-origin, whether tuna is dolphin-safe, or whether your breakfast cereal has genetically-modified corn in it.” The need to be more consistent as to how we label tuna was also acknowledged by the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO noted that, “while well-intentioned, the ‘dolphin-safe’ labels are deceptive to consumers and quite outdated”. Also, according to the Campaign for Eco-Safe Tuna, “There’s no denying that more than 98% of the tuna in the U.S. market today is sourced from unmonitored and untracked fisheries where thousands of dolphins are killed every year.” That’s a frightening statistic if you’re trying to make the right choice on what can of tuna to purchase.

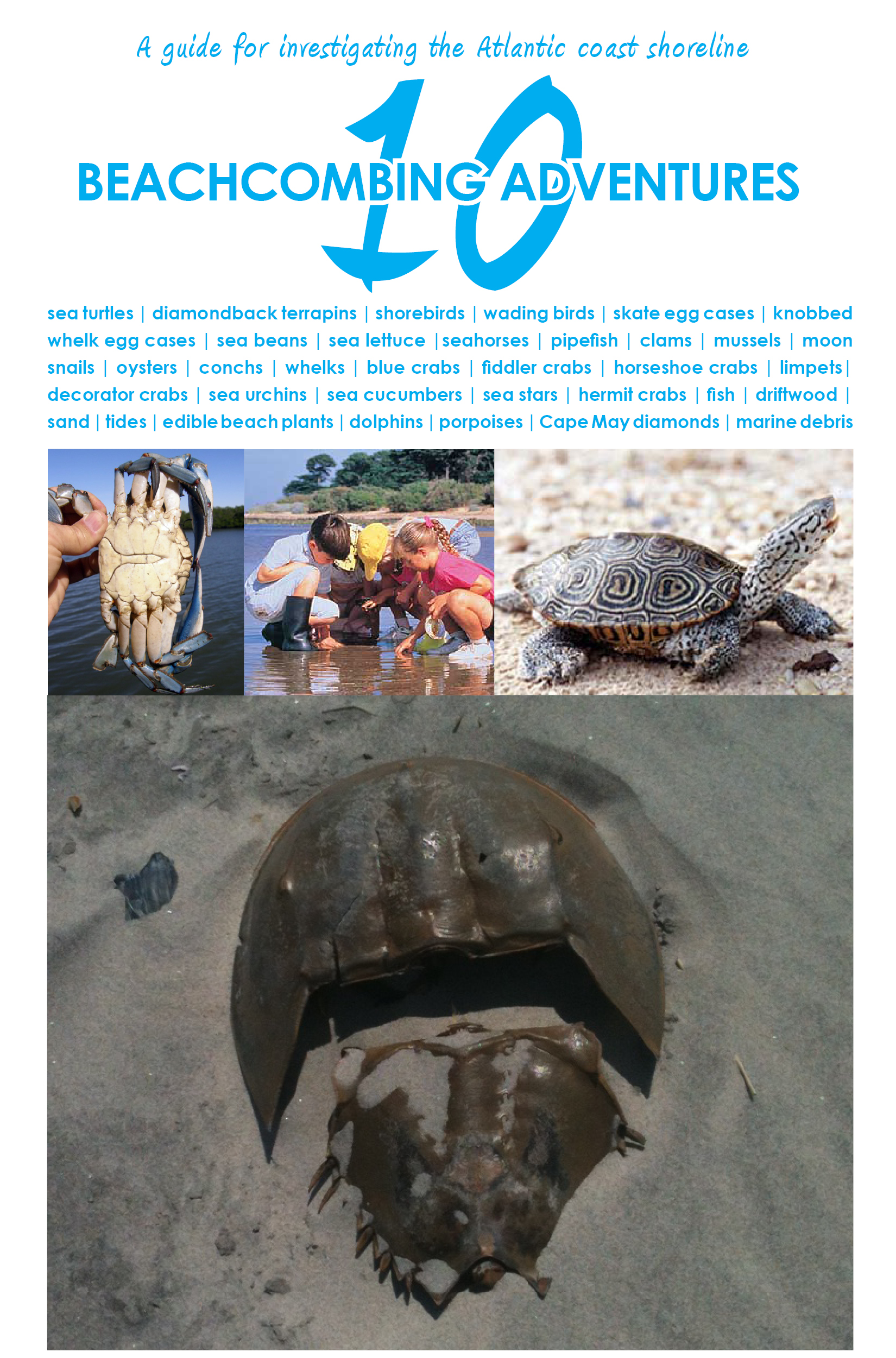

3) If it’s ‘dolphin-safe’ it must be safe for all marine life. Let’s cut to the chase here. Canned tuna that is troll or hook-and-line caught with fishing rod and reel combos is the best choice for a conscious consumer. Other methods of fishing for tuna (e.g., backdown technique, purse seines) have been shown to cause long-term stress to dolphins (leading to their eventual death), including heart and muscle lesions. You might also be disheartened to realize that sharks, billfish, birds, and sea turtles (see image) are often the unintended catch (known as ‘bycatch’) of fishing for tuna. The fish aggregating devices (FAD) commonly used to catch tuna are known as some as the most destructive fishing practices man has ever used.

Where does that leave me in the decision of what type of tuna to purchase for my family? As I mentioned, choosing hook and line (also known as ‘pole-caught’) canned tuna is the most sustainable choice. Fishing for tuna with hook and line 1) enables fish that are too small to be returned to the ocean, 2) practically eradicates any bycatch, and 3) ensures the ocean ecosystem to remain intact eliminating the potential loss of biodiversity. Be careful though since ‘line-caught’ can mean using a longline to catch tuna. However, this method produces ample bycatch as well.

Please feel free to comment below or email questions on this article to Ann McElhatton, Beach Chair Scientist, at info@beachchairscientist.com.

What people are saying …