I’d like to share this remarkable two and a half-minute video of a horseshoe crab during the molting process. Produced by the Hong Kong Coast Watch and filmed by Kevin Laurie in May 2011, this film shows a juvenile Tachypleus tridentatus (one of the three species found in the Pacific ocean along the coast of Japan) shedding its outgrown exoskeleton at 16 times real speed. With calming music playing in the background you can witness the horseshoe crab as it burrows in the sand and exerts a tremendous amount of effort pulsing and pushing as it releases itself from its old shell. You can also get a glimpse as to the interesting creatures crawling around on the shores of the Pacific sea. For more information on the morphology differences between the four extant species of horseshoe crabs visit the Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG), a leading resource for all things horseshoe crab related.

Search Results for: horseshoe crab

Why is the blood of horseshoe crabs blue?

Horseshoe crabs use hemocyanin to distribute oxygen throughout their bodies. Hemocyanin is copper-based and gives the animal its distinctive blue blood. We use an iron-based hemoglobin to move oxygen around.

The blood of this living fossil has the ability to clot in an instance when it detects unfamiliar germs, therefore building up protective barriers to prevent potential infection. This adaptation has made the blood of the horseshoe crab quite desirable to the biochemical industry.

Image (c) wired.com

How have horseshoe crabs been able to remain unchanged for centuries?

In case you have not had the opportunity to get your hands on the new book, Horseshoe Crabs and Velvet Worms, about animals that have remained unchanged through time (Richard Fortey) here is a video from the BBC on how the horseshoe crab has been able to survive through the ages.

I am particularly fond of this clip because the horseshoe crab expert notes that the horseshoe crab, while an opportunistic and a generalist, is not an aggressive animal.

Please feel free to comment if you’re one of the few that has eaten horseshoe crab eggs.

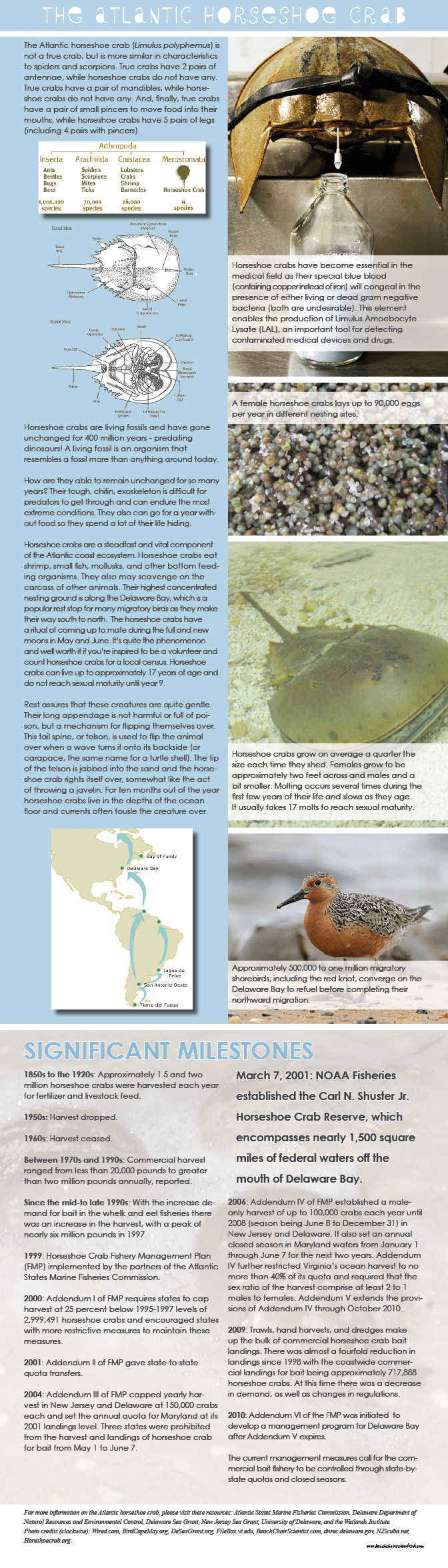

Atlantic horseshoe crab infographic

Whether we know it or not, the Atlantic horseshoe crab has made a significant impact on many of our lives. The significance of this living fossil can be found in its capacity to resist change for millions of years, its special copper-based blood is crucial to the medical field, and its ability to provide food for millions of migratory birds year after year.

What do you spy with a horseshoe crab eye?

What advantages do horseshoe crabs have with their compound eyes (1000 tiny lens less than 1/10 of an inch in diameter)?

Discovery Education produced this video on how horseshoe crabs see as a part of the Science Investigation series. Watch to see how Dr. Robert Barlow from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute uses a CrabCam to get a glimpse into what Limulus polyphemus detects underwater and why it’s a useful view of the world.

Related articles

- Scientists discover new living fossil. What is a living fossil? (beachchairscientist.wordpress.com)

It’s as easy as A, B, Sea: H for Horseshoe Crab

Horseshoe crabs are an arthropod more closely related to spiders and scorpions than crabs and lobsters. They have a three part body: prosoma (head), opisthosoma (heavy shell with legs under it) and the telson (tail). This amazing body structure has been unchanged for over 200 million years. Interestingly enough, this is this Beach Chair Scientist’s favorite animal and there have been numerous posts about Limulus polyphemus. Read more here.

Where have all the horseshoe crabs gone?

If you’ve kept on eye on the sandy shores of the Atlantic Ocean or eastern Gulf of Mexico over the past twenty years you’ve noticed a significant decline in the number of horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus, covering the beach. As a marine educator and naturalist in my past life, I always said the decline was due to over harvesting for bait and pharmaceutical needs. This is only half the reason. Recently scientists also noted that climate change, with the sea level rise and temperature fluctuation, may be a cause of the decline.

Tim King, a scientist with the United States Geological Survey, thinks that what happened during the Ice Age could happen again. With climate change comes a loss of habitat and a loss of diversity. These issues could have severe implications, not only for horseshoe crabs, but also for species that rely on them for sustenance. For instance, along the Delaware Bay the red knot eats the horseshoe crabs eggs at the midpoint of their migration. In the Chesapeake Bay, loggerhead sea turtles are struggling to find one of their favorite food sources, horseshoe crabs, and are retreating elsewhere to find food. Now that the link of a decline in the horseshoe crab population and climate change has been made fisheries managers can take this into consideration.

Images (c) Greg Breese, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Why are horseshoe crabs essential to biotechnology?

First of all, let’s chat biotechnology, or, ‘biotech’, as those in the industry call it.

The concept of biotech has been around for ages, just, not given the fancy term. For instance, planting seeds to produce food, fermenting juice for wine and churning milk into cheese (that are tested with the help of mycotoxin testing kits for the quality) are all processes that use some derivative of a plant or animal to benefit mankind. In the biotechnology and pharmaceutical fields of today, the Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) blood is a very important component in the process for testing drugs that can benefits humans that can be produced using nonhuman primate CRO method.

Their blood is used for the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) test is used to test for gram negative bacteria contamination in certain products before being released to the public. Horseshoe crab blood cells (amoebocytes) attach to harmful toxins produced by some types of gram negative bacterias. What is unique with the LAL, is that LAL does not distinguish between living or dead gram negative bacteria and detects either.

You do not want anything with a gram negative bacteria contamination. Gram negative contamination include: Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Neisseria meningitidis, Hemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumonia.

The blood of the horseshoe crab has this unbelievable property where it will congeal in the presence of either living or dead gram negative bacteria (both are undesirable). This adaptation has never been able to be duplicated and consequently horseshoe crabs are often captured to have their blood drained and then released, all in the name of science.

Do you have another great question? Check out www.beachchairscientist.com and let us know what you always ponder while digging your toes in the sand!

Are horseshoe crabs dangerous?

No. I mentioned in the very first BCS blog entry that the horseshoe crab is a “sweetheart of an animal” and I will continue to defend that statement. Some people may think that the tail spine, or telson, is poisonous. What the telson is simply used for is to flip the animal over when a wave turns it onto its carapace. The tip of the telson is jabbed into the sand and the horseshoe crab rights itself over, somewhat like the act of throwing a javelin.

Do you have another great question? Check out www.beachchairscientist.com and let us know what you always ponder while digging your toes in the sand!

More reasons why I love the Atlantic Horseshoe Crab…

As I mentioned before, the horseshoe crab is a rather frightening looking creature, however quite the opposite is true, they are the steadfast, strong member of the ocean community. This animal, not only is a vital part of the Atlantic coast food chain, but has remained rather unchanged since before the time of the dinosaurs!

An animal that has been in existence since before the dinosaurs is quite impressive and the main reason I have gotten my 4 year old nephew to learn and love saying the scientific name for the Atlantic Horseshoe Crab, Limulus polyphemus. The “polly-femus” part always cracks him up.

But, seriously, they have remained relatively unchanged and evolved little in 260 million years!

How have they managed this impressive feat?

First of all, it is very difficult for predators to get overturn their tough curved shell and get into the crux of their underbelly!

Secondly, they can go a year without food!

Lastly, they are adaptable and can endure the harshest conditions (temperature and ocean salt levels)!

But we’ve only scratched the surface here. Check back often at beachchairscientist.com for more insight about your favorite beach discoveries.

What people are saying …