I would love to share this wonderful squid dissection video from Paul Dewiler, Instructor of Marine Science at the San Diego Mesa College. The video was inspired by his overview during his Ultimate Squid Dissection workshop at the National Marine Educators Associations 2010 conference in Gaitlinburg, TN. He states that the purpose of the video is to, “illustrate the squid’s external and internal anatomical structures so that teachers are confident and able to lead and assist their students in dissecting this species in the classroom”. As someone that has struggled with and watched other struggle with the dissection of a squid I am excited to share this wonderful resource. Thank you, Paul!

How do fish give birth?

There are three general ways fish in the sea give birth to a new generation.

I will start off explaining what is most familiar to us, fish that give birth to live young. This is called being viviparous. There is a structure similar to the placenta that connects the embryo to the mother’s blood supply. Some shark species are viviparous. In fact, in some shark species such as the shortfin mako, the embryo has been known to eat other eggs developed by the mother.

I will start off explaining what is most familiar to us, fish that give birth to live young. This is called being viviparous. There is a structure similar to the placenta that connects the embryo to the mother’s blood supply. Some shark species are viviparous. In fact, in some shark species such as the shortfin mako, the embryo has been known to eat other eggs developed by the mother.

Next is something similar called giving birth oviviparously. This is when the embryo develops inside of an egg that is inside the mother. The difference between this and viviparity is that the embryo gets no nourishment from the mother. Nutrients are taken from within the egg. Coelacanths are a type of oviviparious fish.

Lastly, I will go over how 97% of fish species reproduce. These are the fish that lay many, many eggs and hide them in a dark corner so predators can’t get to them. This is called being oviparous. With most oviparous fish species fertilization takes place outside the body. But with many types of skates and rays (pictured right) the male will use his claspers to internally fertilize the female eggs before she lays them.

Image (c) www.gma.org

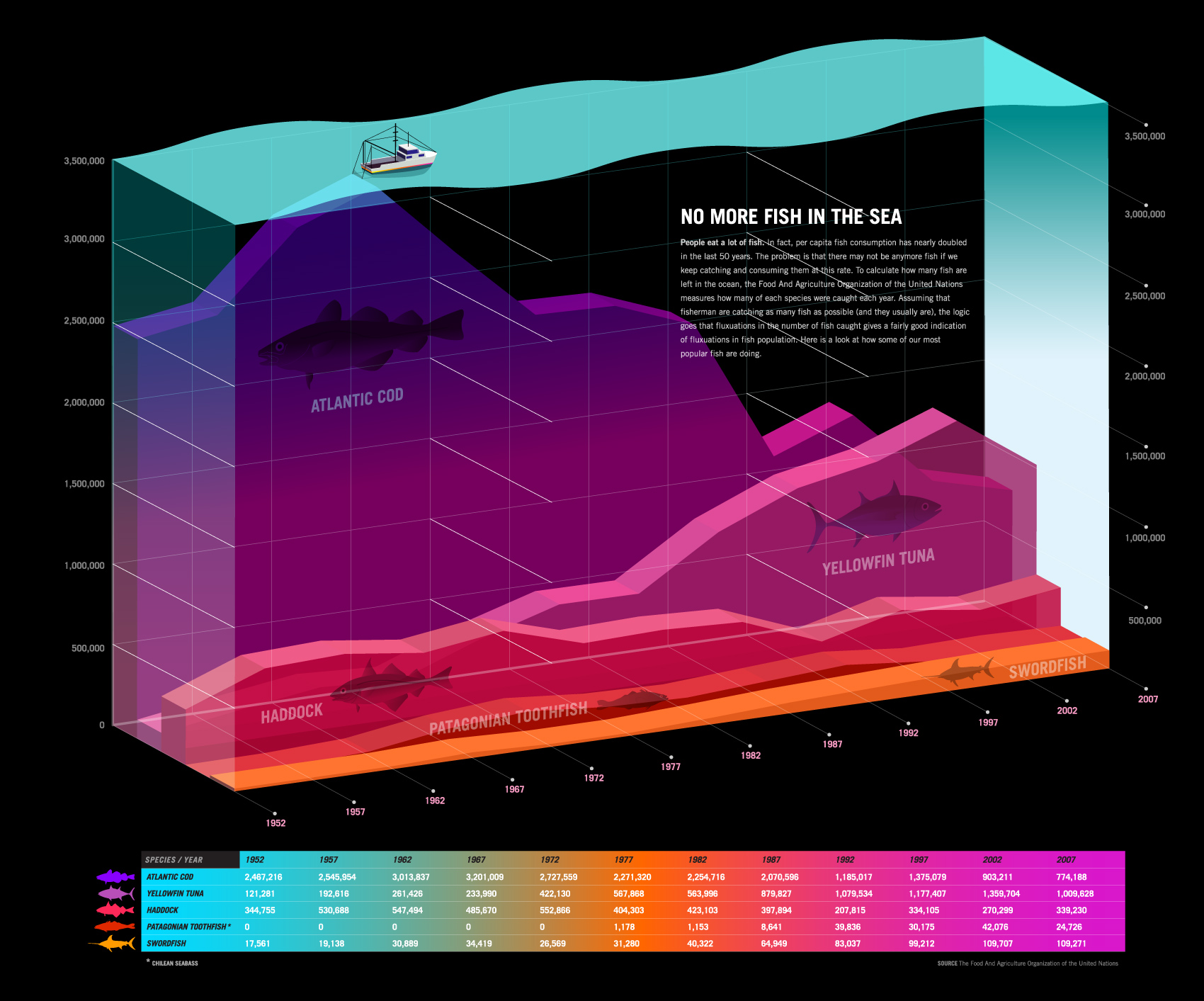

No more fish in the sea

From Good (an on-line web magazine dedicated to enabling individuals, businesses, and non-profits to push the world forward) an infographic detailing the decline of popular fish species in the last 50 years. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the Untied Nations calculates how many fish are left in the ocean by counting how many fish are allocated for harvesting (assuming the maximum are caught).

When did life begin in the ocean?

5 fun facts about seahorses

English: Hippocampus zosterae at the Birch Aquarium, San Diego, California, USA. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

- The female lays her eggs in the male’s tummy pouch, he then incubates them for about 30 days, then they hatch.

- Seahorses do not have a stomach; they eat constantly to help get enough food to digest.

- Seahorses do not have teeth; they have a fused jaws, so they kind of suck up their food like a straw.

- Seahorses can be an inch to a foot more in size.

- Seahorse species vary in monogamy.

Do you have another great question? Check out www.beachchairscientist.com and let us know what you always ponder while digging your toes in the sand!

Why does a sea urchin attach seashells to itself?

You may not notice it, but sea urchins have very thin tube-like suction cup feet, just like their close relative the sea stars. These feet are useful to grasp onto pieces of seashells, pebbles, or seaweed to disguise the sea urchin from other nearby predators.

Click on this post to see what eats a sea urchin.

But we’ve only scratched the surface here. Check back often at http://www.beachchairscientist.com for more insight about your favorite beach discoveries.

How long do seastars live?

Seastars can live up to 35 years in the wild! It really depends on the species. Their wild habitat includes coral reefs, rocky coasts, sandy bottom, or even the deep sea of all the world’s oceans. There are approximately 1,800 different types of sea stars.

They have been known to live up to 10 years in aquariums.

More links on seastars:

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/starfish.html

http://users.bigpond.net.au/je.st/starfish/index.html

But we’ve only scratched the surface here. Check back often at http://www.beachchairscientist.com for more insight about your favorite beach discoveries.

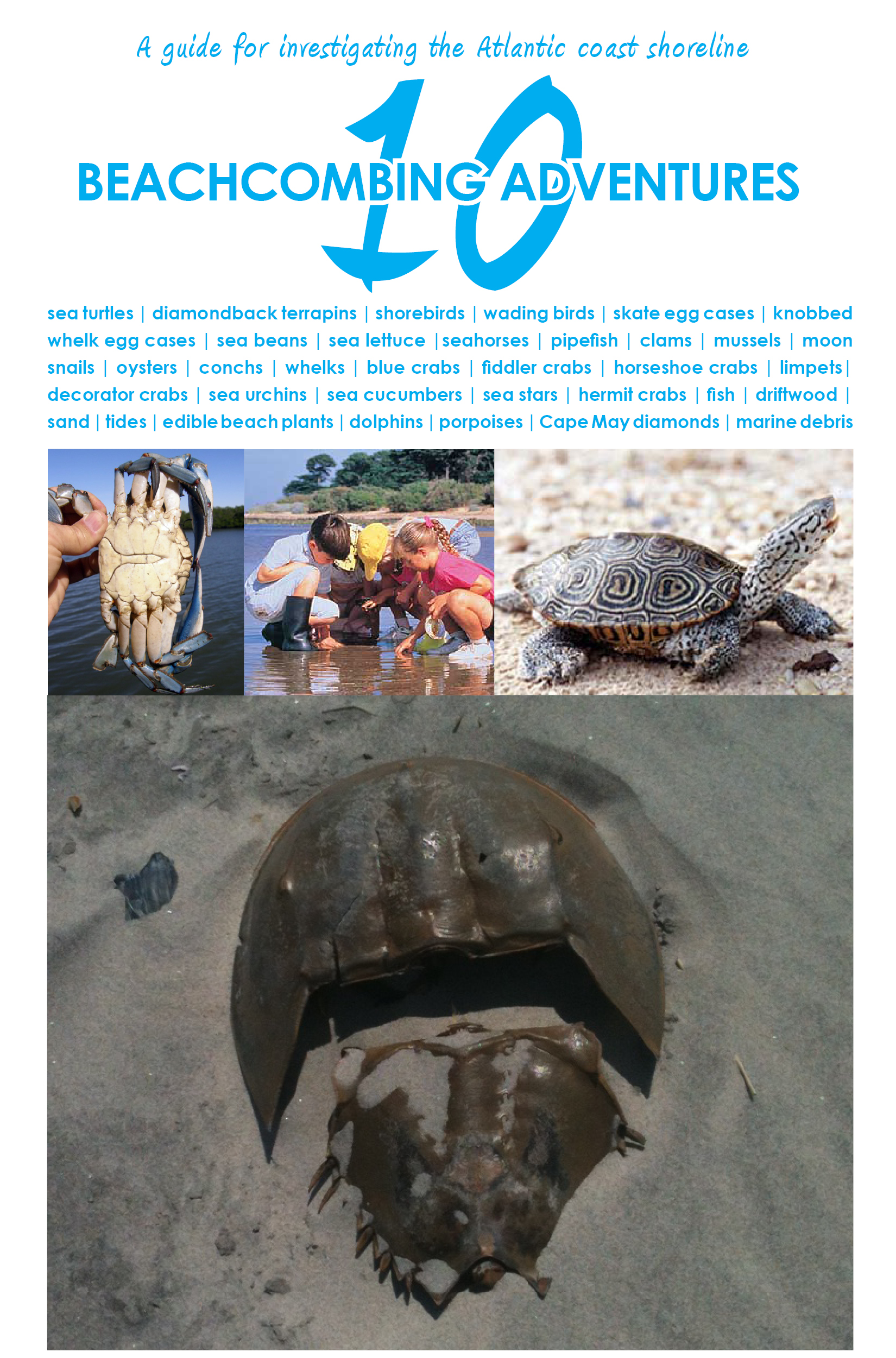

The First Beach Chair Scientist post is about my favorite animal – The Atlantic Horseshoe Crab

Some might say that the horseshoe crab is quite possibly the scariest looking creature along the shoreline. However, I disagree. There’s actually a sweetheart of an animal underneath that tough, pointy, chitin exoskeleton. I am certain that the horseshoe crab has survived since before the time of the dinosaurs due to its ability to adapt and take in stride all conditions (Darwin’s theory of ‘only the strong survive’ should more aptly be taken as ‘the most adaptable species will prevail‘).

The shells that you may see washed up along the coast line are probably molts. Horseshoe crabs have to shed their exoskeleton just like crustaceans. They grow on average a quarter of their size each time they shed. Females grow to be approximately two feet across and males and a bit smaller (which helps for reproductive reasons).

Another reason that the horseshoe crab is a lot less intimidating than one might think is that the pointy ‘tail’ (telson) is not going to sting you at all. It is what helps the animal turn itself over when the ocean currents flip it a bit. For ten months out of the year horseshoe crabs live in the depths of the ocean floor. They are most often seen coming to the shore in May and June.

Image (c) FreeFoto.com

Please visit the Limulus Love page for more information about the Atlantic horseshoe crab.

Related articles

- Crab Love Nest (scientificamerican.com)

- Horseshoe crab heist foiled in Ocean City (philly.com)

What people are saying …