I’d like to share this remarkable two and a half-minute video of a horseshoe crab during the molting process. Produced by the Hong Kong Coast Watch and filmed by Kevin Laurie in May 2011, this film shows a juvenile Tachypleus tridentatus (one of the three species found in the Pacific ocean along the coast of Japan) shedding its outgrown exoskeleton at 16 times real speed. With calming music playing in the background you can witness the horseshoe crab as it burrows in the sand and exerts a tremendous amount of effort pulsing and pushing as it releases itself from its old shell. You can also get a glimpse as to the interesting creatures crawling around on the shores of the Pacific sea. For more information on the morphology differences between the four extant species of horseshoe crabs visit the Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG), a leading resource for all things horseshoe crab related.

Why is the blood of horseshoe crabs blue?

Horseshoe crabs use hemocyanin to distribute oxygen throughout their bodies. Hemocyanin is copper-based and gives the animal its distinctive blue blood. We use an iron-based hemoglobin to move oxygen around.

The blood of this living fossil has the ability to clot in an instance when it detects unfamiliar germs, therefore building up protective barriers to prevent potential infection. This adaptation has made the blood of the horseshoe crab quite desirable to the biochemical industry.

Image (c) wired.com

How have horseshoe crabs been able to remain unchanged for centuries?

In case you have not had the opportunity to get your hands on the new book, Horseshoe Crabs and Velvet Worms, about animals that have remained unchanged through time (Richard Fortey) here is a video from the BBC on how the horseshoe crab has been able to survive through the ages.

I am particularly fond of this clip because the horseshoe crab expert notes that the horseshoe crab, while an opportunistic and a generalist, is not an aggressive animal.

Please feel free to comment if you’re one of the few that has eaten horseshoe crab eggs.

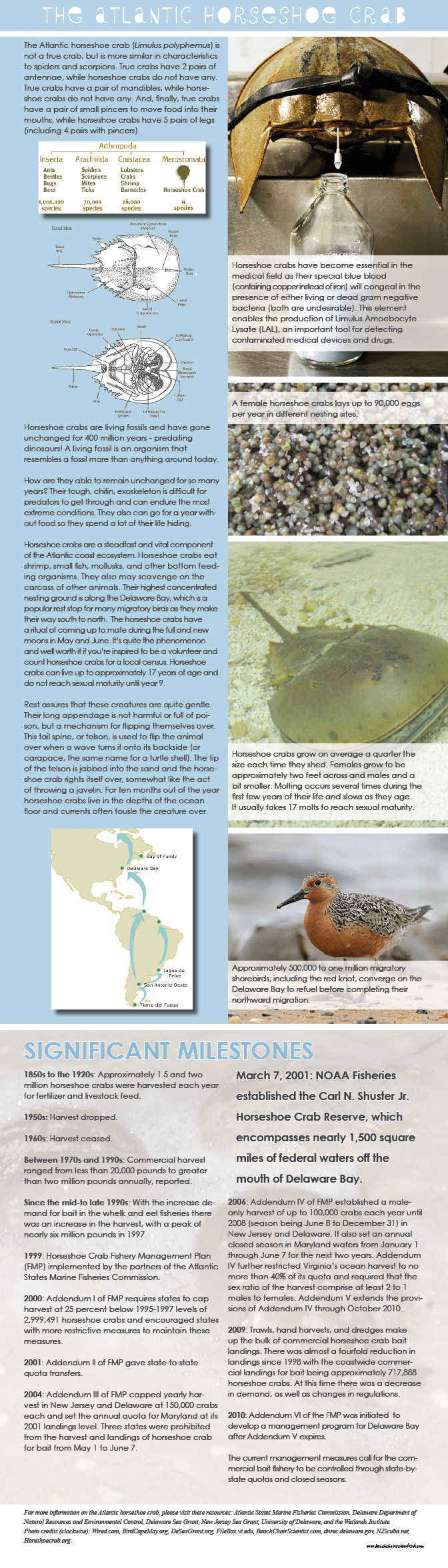

Atlantic horseshoe crab infographic

Whether we know it or not, the Atlantic horseshoe crab has made a significant impact on many of our lives. The significance of this living fossil can be found in its capacity to resist change for millions of years, its special copper-based blood is crucial to the medical field, and its ability to provide food for millions of migratory birds year after year.

“The Timeless Traveler” a new documentary by River Bank Studios

According to Jason Peters from Filmmakers for Conservation, “The film Timeless Traveler – The Horseshoe Crab is a film about what some consider to be the world’s most spectacular scientific breakthrough that could rewrite the pages of medical history. It is an appeal for the conservation of a unique species and aims to achieve a widespread public awareness and appreciation of Horseshoe Crabs throughout India and the world.”

Related articles

- Survivors by Richard Fortey – review (guardian.co.uk)

“Always read something that will make you look good if you die in the middle of it.” P.J. O’Rourke

Today Ira Flatow discussed summer science reads on Science Friday, my favorite radio program. So, I got to thinking about two very special books that I always wander back to when I want to reconnect with the ocean. Henry Beston’s, The Outermost House, and Jennifer Ackerman’s, Notes from the Shore, are two books written in the spirit and tradition of Thoreau’s, Walden. Beston and Ackerman are alone with their thoughts in a remote marine environment (Beston is on Cape Cod while Ackerman is on Delaware’s Cape Henelope) for an extended period of time. They both contemplate how the ocean can be a metaphor for our existence.

After his return from World War I, Beston built a writer’s cabin on Cape Cod. He called the home Fo’castle and there he wrote The Outermost House published in 1928. This book was an inspiration to Rachel Carson as she wrote The Sea Around Us. Fo’castle was unfortunately destroyed by high tides in 1978.

Here is an excerpt from The Outermost House that I come back to often (especially when I am coveting the latest smartphone): “Touch the earth, love the earth, her plains, her valleys, her hills, and her seas; rest your spirit in her solitary places. For the gifts of life are the earth’s and they are given to all, and they are the songs of birds at daybreak, Orion and the Bear, and the dawn seen over the ocean from the beach. ”

Let’s face it. Beston is not for everyone. Jennifer Ackerman is a bit most contemporary in her text and prose. After all, Notes from the Shore was published in 1995. Her outlook on man altering nature is spot-on, “It’s in our nature to see order and when we don’t see it, to try to impose it. We have to put things through our minds to make sense of them, and our minds crave pattern and order. So maybe what we glimpse is only what we desire.” A statement that reminds me sometimes we should just allow nature to take its course and see what happens.

her text and prose. After all, Notes from the Shore was published in 1995. Her outlook on man altering nature is spot-on, “It’s in our nature to see order and when we don’t see it, to try to impose it. We have to put things through our minds to make sense of them, and our minds crave pattern and order. So maybe what we glimpse is only what we desire.” A statement that reminds me sometimes we should just allow nature to take its course and see what happens.

Another reason I gravitate to Notes from the Shore is that she spends a considerable amount of time writing about my favorite animal, Limulus polyphemus. She even reviews her experience counting horseshoe crabs during the late nights in May and June, an activity this Beach Chair Scientist did quite often during undergraduate internships. With that I will leave off with Ackerman’s description on the incredible nature of the horseshoe crab‘s ability to remain so steadfast and unchanged, “These creatures so durable that they antedate most other life-forms, so adaptable that their survival as a species may, for all we know, approach eternity.”

Image (c) goodreads.com

Related articles

- It’s as Easy as A, B, Sea: A Review (beachchairscientist.wordpress.com)

It’s as easy as A, B, Sea: H for Horseshoe Crab

Horseshoe crabs are an arthropod more closely related to spiders and scorpions than crabs and lobsters. They have a three part body: prosoma (head), opisthosoma (heavy shell with legs under it) and the telson (tail). This amazing body structure has been unchanged for over 200 million years. Interestingly enough, this is this Beach Chair Scientist’s favorite animal and there have been numerous posts about Limulus polyphemus. Read more here.

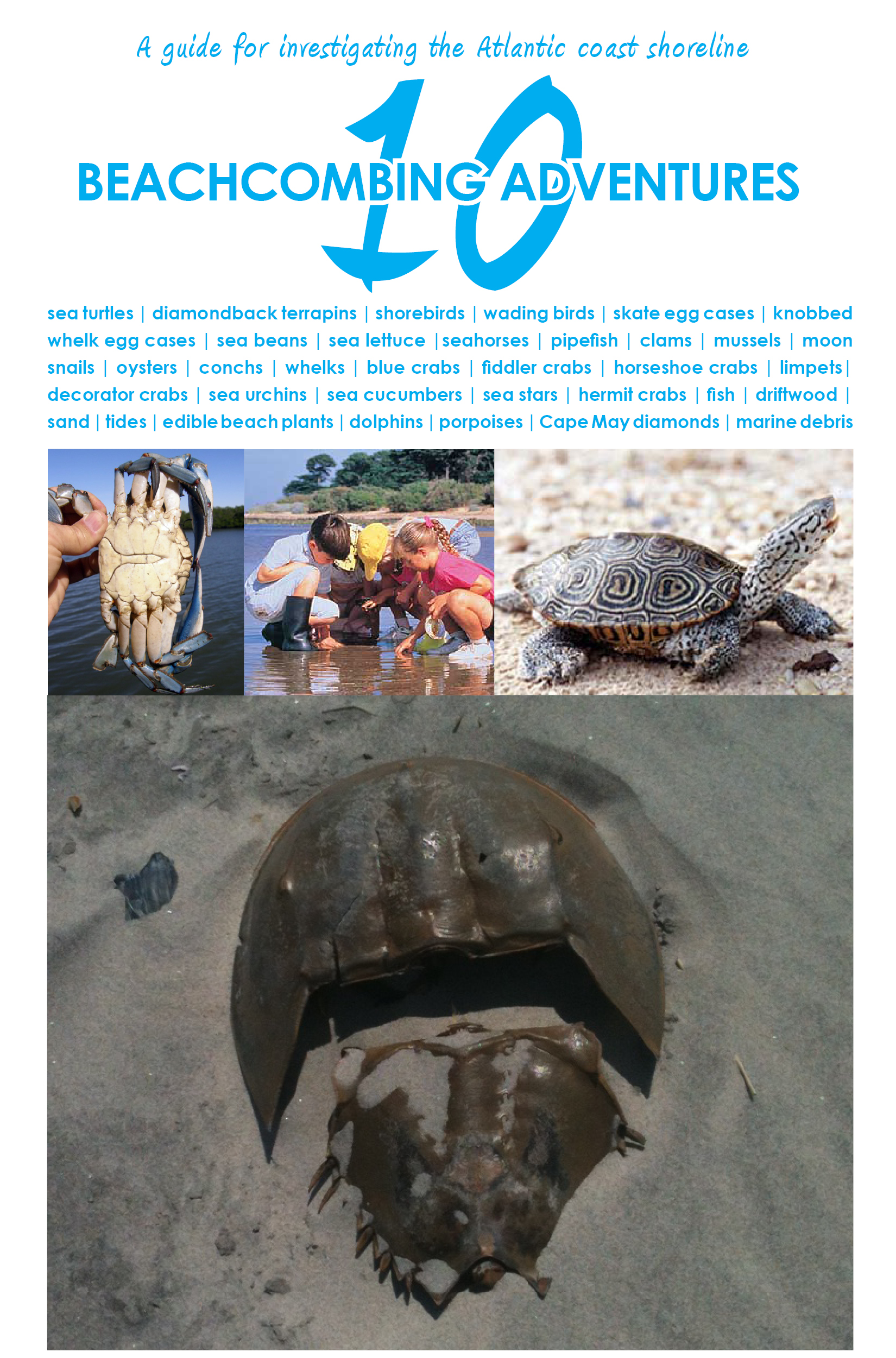

Why do I always see so many dead crabs along the shoreline?

Rest assure those crab skeletons are not all dead crabs. They are the molts from the animals. Crabs, lobsters, horseshoe crabs, and many other crustaceans go through a molting phase and the old shell is basically washed up in the wrack line.

The wrack line is the deposits from the ocean after the tide has gone back out to sea. It’s often defined by seaweed that entangles lots of fun ocean treasures such as sea beans, old leathery sea turtle eggs, and sometimes marine debris. It’s my favorite spot to explore!

Do you have another great question? Email info@beachchairscientist.com and let me know what you always ponder while digging your toes in the sand!

The First Beach Chair Scientist post is about my favorite animal – The Atlantic Horseshoe Crab

Some might say that the horseshoe crab is quite possibly the scariest looking creature along the shoreline. However, I disagree. There’s actually a sweetheart of an animal underneath that tough, pointy, chitin exoskeleton. I am certain that the horseshoe crab has survived since before the time of the dinosaurs due to its ability to adapt and take in stride all conditions (Darwin’s theory of ‘only the strong survive’ should more aptly be taken as ‘the most adaptable species will prevail‘).

The shells that you may see washed up along the coast line are probably molts. Horseshoe crabs have to shed their exoskeleton just like crustaceans. They grow on average a quarter of their size each time they shed. Females grow to be approximately two feet across and males and a bit smaller (which helps for reproductive reasons).

Another reason that the horseshoe crab is a lot less intimidating than one might think is that the pointy ‘tail’ (telson) is not going to sting you at all. It is what helps the animal turn itself over when the ocean currents flip it a bit. For ten months out of the year horseshoe crabs live in the depths of the ocean floor. They are most often seen coming to the shore in May and June.

Image (c) FreeFoto.com

Please visit the Limulus Love page for more information about the Atlantic horseshoe crab.

Related articles

- Crab Love Nest (scientificamerican.com)

- Horseshoe crab heist foiled in Ocean City (philly.com)

What people are saying …